We recently wrote about the things we value as a writing teacher. Most of the things I listed were the usual “teacher-y” ideas such as complete thoughts with correct spelling and punctuation. But down at the very bottom of the list, I also included “real interest and engagement in the writing process.” Two of my biggest take-aways from the past two semesters are that students must value writing and I must trust in my ability to see value and opportunities in their writing. One way to share value is to give ownership of the process back to my students. With this thought in mind, I gathered a group of volunteers to help me construct a checklist for an animal research project. I thought they would be very willing to contribute, vocalizing their ideas faster than we could write them all down. But I was confronted with blank stares and silence. They didn’t trust me at all. That’s when it hit me. These students didn’t feel valued as writers. I had spent the last seven months with these writers, and I had failed to instill confidence or cultivate an atmosphere of mutual respect. After all their years of writing, they still saw writing as the domain of teachers. They expected to be told what to write and how to write it. They didn’t have the faintest idea of how to even begin to contribute their own ideas. It was a slow, painstaking process, but I was finally able to convince them that I wasn’t joking, that I sincerely wanted their input. I listened as they tentatively suggested ideas, cringing as I heard the reluctance and uncertainty in their voices. I couldn’t help but think of the enthusiastic voices that I see and hear in the pre-k and first grade classrooms and wonder when that ends.

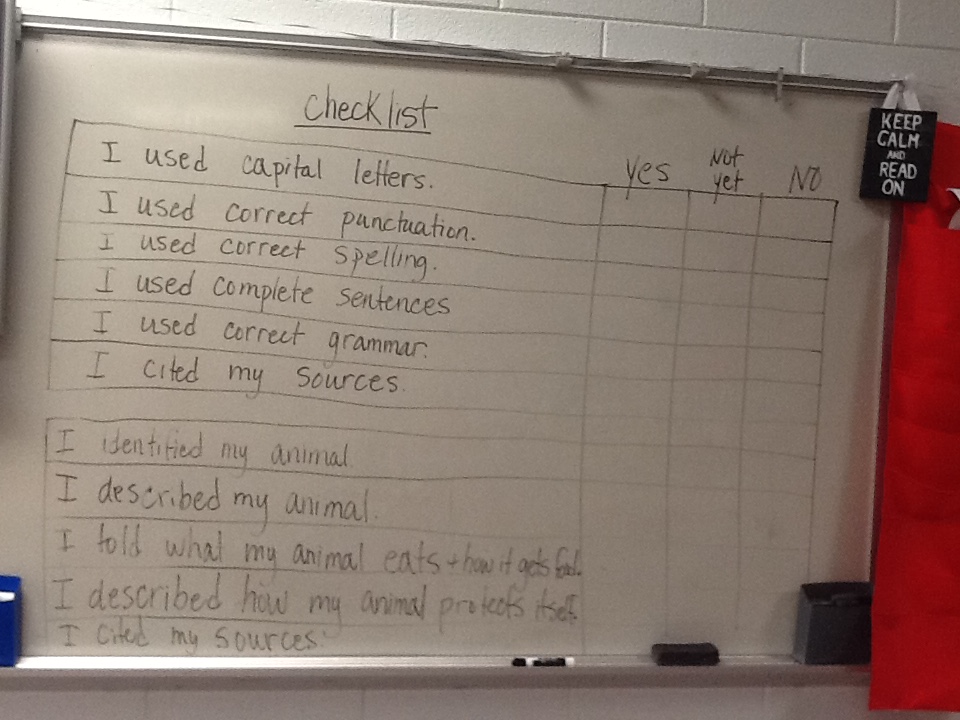

Here is the first draft of our checklist:

We still have a lot of work to do, but this is a good start.

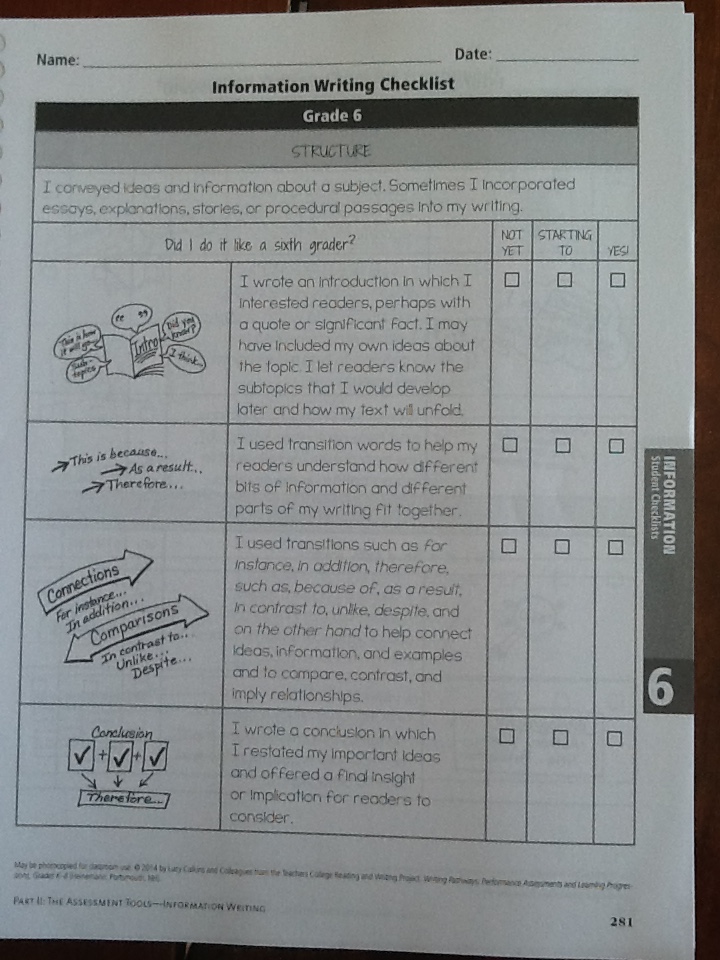

Notice the use of the Yes and No columns. These were their ideas. I briefly talked about how we could use language that didn’t make a harsh judgment that could discourage writers who may be struggling, but they were not ready to change their thoughts on this just yet. They still think, like I did, from a deficit view. I want to share the checklists from Lucy Calkins’s Writing Pathways.

I could begin to shift their thinking from a yes or no viewpoint to a “not yet” and “beginning to” mind-set. No just sounds so final. The students seem to see that x in the no column and confirm their belief that they are just not a good writer. It gives them the excuse they need to quit and give up before they can be told they aren’t good enough again. This line of thinking made me remember the article I read by S. M. Brookhart. Brookhart, S. M. (2013, December). Develop a student-centered mind-set for formative assessment. Voices from the Middle, 21(2), 21-25. “The teacher used strategies for getting the descriptions in the rubrics inside the kids’ heads. Those strategies included using the rubrics from the outset, centering lessons on one important aspect of writing, harnessing the power of students’ talking together to develop an abstract concept like ‘ideas,’ encouraging peer editing, and coaching students to keep their discussions and editing work trained on that one aspect.” If I can get students to think about the process of writing as they are writing, they can use these checklists and rubrics as a type of road map to get them to their writing destinations.

I love that you got input from your students to create a rubric for their project. I’m sure it also gives them more meaning and ownership having come up with what is important for their project. And using the Not Yet column for a piece in progress.. wow! What a great idea to keep them encouraged and having doable goals to work toward. Awesome, Roxy!

LikeLike

What struck me in this post was how you interpreted students’ reluctance to help you construct the rubric. Rather than see students as “lazy” or “disinterested” or “apathetic,” you saw students as scared and hesitant. By the time they’re in middle school, students have learned that assessment is the teacher’s responsibility; if you’re ‘good’ writer, assessment is seen as a positive process that builds confidence, but if you’re a struggling/’striving’ writer, assessment can be seen as a form a punishment. You’re essentially exploring how teachers can revise their own classroom routines and practices to invite students into taking a greater role in assessment and how this impacts the writing process itself. This is empowering to both students and teachers!

We all deserve to see our work as “developing” (i.e., “not yet”) rather than simply putting a “yes/no” label on it. I encourage you to see your own work as a writing teacher this way too. Give yourself a chance to exist in the “not yet” column, because, as you suggest in the post, this is where REAL learning occurs.

I also want to say that I appreciate how you borrowed ideas from the readings (e.g., Calkins, Brookhart) but ultimately made this lesson your own based on the needs of your YOUR students. Sure, Calkins’ rubric sounds/looks great, but the more important part right now is that your students feel included in the process. I look forward to seeing how this tool (and additional mini-lessons) help students “think about the process of writing as they are writing… to get them to their writing destinations.” This could be a powerful focus of a PD workshop!

LikeLike

I can picture your students’ blank stares as I am reading your post. Of course we get blank stares and of course they think you are playing a joke on them…..It’s what we, as teachers, have taught them for the last several years. We tell them everything we need to write and then all of a sudden we are asking them to tell us what things are important when writing.

I enjoyed your “I’m not going to give up” attitude and how you worked with the students to come up with a rubric for their on writing! Thanks for sharing….I should do this with my little ones!

LikeLike